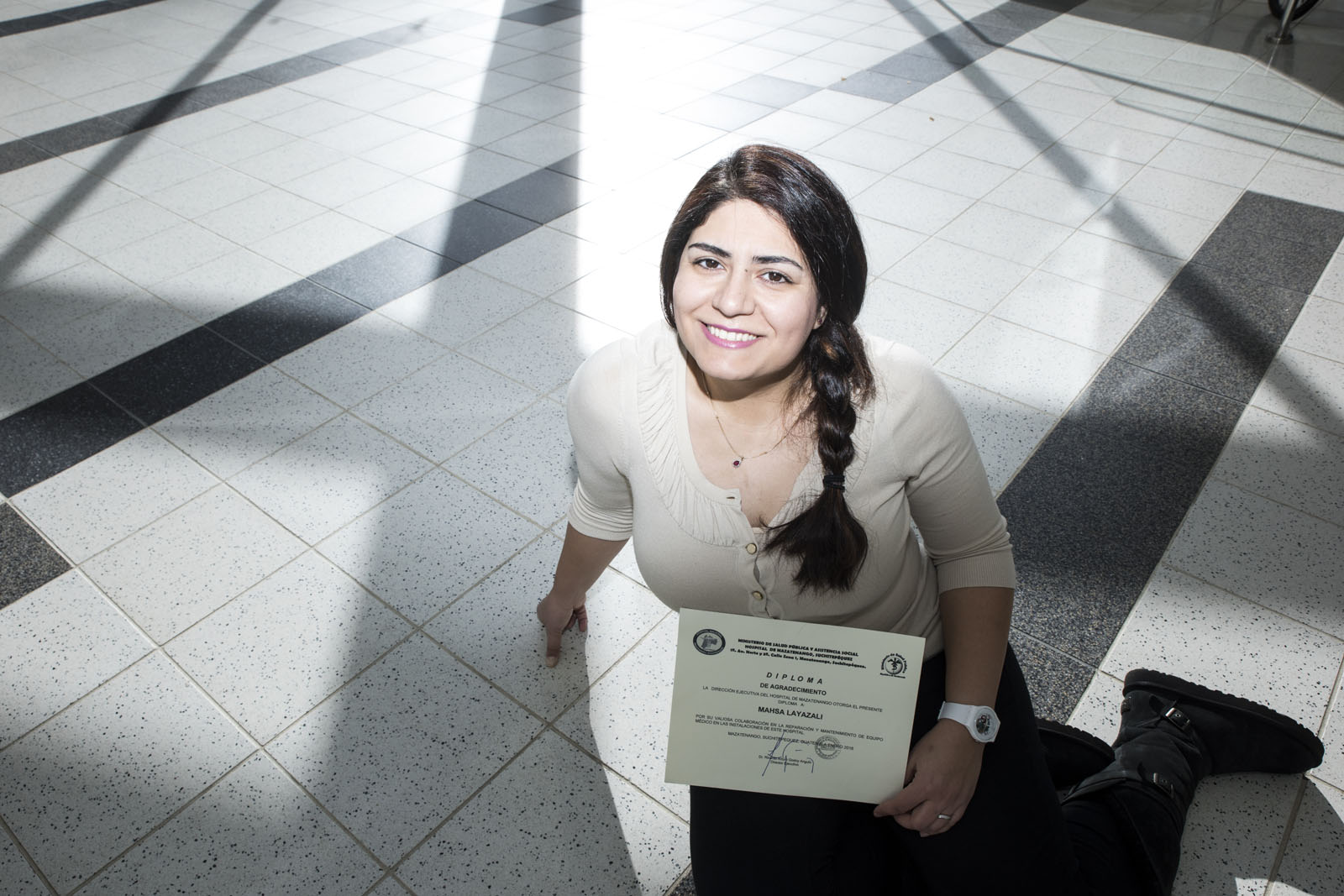

After a winter 2015 trip to Guatemala, where she helped repair and maintain medical equipment, Mahsa Layazali, a bioengineering major who is graduating in December, hopes to return to the country one day to do that work full time. Photo by Ron Aira.

When Mahsa Layazali and her co-workers received the skin grafting device to repair, it needed a thorough washing, as it had just been used during a dermatological procedure—like, right then.

The blood and remnants of skin didn’t bother Layazali. She did wonder, though, how the surgeon, now without a key piece of equipment, completed the procedure.

“He was skilled,” the George Mason University senior said. “He found another way.”

The three weeks that Layazali spent with three classmates maintaining and repairing medical equipment in Mazatenango, Guatemala, last winter were full of such stories. But the experience also set a long-term career vision for the bioengineering major who is graduating this month.

“I’m not surprised,” said Claudia Borke, Layazali’s academic advisor. “She was so touched. She had some experiences that really changed the way she’s going to walk down her life path.”

Layazali, 31, came to the United States in 2008 from Iran, where she said she was prohibited from attending college because of her Bahá’í religion. Sponsored by her uncle, she joined her sister, Malahat, who emigrated previously and graduated from George Mason in 2006 with a management degree.

It was Malahat’s recommendation that helped push Layazali to Mason after two years at Northern Virginia Community College. Layazali’s husband, Saman Refaei, will transfer from NOVA to Mason in the spring as a management major.

“It was a good choice for me,” Layazali said. “It worked perfectly.”

Her trip to Guatemala, through the organization Engineering World Health and the Bioengineering Department in Mason’s Volgenau School of Engineering, was transformative.

The hospital had equipment donated from the United States, but had few manuals explaining their use. With a semester’s-worth of training through her BENG 499 Bioengineering World Health class, Layazali became part of a service and repair shop, fixing things such as patient monitors and surgical suction devices. Basic manuals, written in Spanish, thanks to her bilingual classmates, were left behind.

“I really felt like we made a change,” Layazali said. “I will never forget the smiles on the faces of the doctors and nurses when the machines started working, how we made them happy and they kept appreciating us.”

Layazali, who is considering medical equipment repair as a career, said she plans to return to the hospital, at least as a volunteer.

“I’d really like to live there,” she said. “I just feel, in general, that country needs help, and they are open to people who try to help them.”